National Music Publishers Association president and CEO David Israelite, keynote speaker at the Production Music Conference in Los Angles, Oct. 4-6. (Photo: Tomorrow Mingtian/PMA)

David Israelite is president and CEO of the National Music Publishers Association, a trade group representing American music publishers and songwriters. Read the complete text of his keynote address at the Production Music Conference here. The NMPA‘s stated mission is “to protect, promote, and advance the interests of music’s creators” by safeguarding members’ property rights on the legislative, litigation, and regulatory fronts as well as laying the groundwork for future best practices. Based in Washington, D.C., David Israelite shared his views on Oct. 5 at the the fourth annual Production Music Conference, Oct. 4-6 at the Loews Hollywood Hotel in Los Angeles.

It’s been five or six years since I spoke to your conference in Las Vegas. I’m going to talk about a lot of different things going on in Washington. Actually, I was out in the hall talking to some folks, and decided to completely scrap what I was going to say and talk instead about things I think may be more relevant to what you want to hear about. The first thing I want to say is I am well aware of a disturbing trend going on in your industry, where your licensees are starting to take what I would call morally questionable requests about what you must give them in order to use their music. This afternoon, Variety will publish an opinion piece I wrote, and I’m going to read you a couple of paragraphs from that piece so you get a flavor of what that piece is going to say:

“Legal issues aside, what’s concerning is the propriety of holding composers hostage to a morally troubling choice. If a composer wants a major network – with enormous market power – to use their work on any of their channels or programs, they are being told they essentially have to allow them to take partial credit for it. Again, what’s being required isn’t just a cut of composers’ money, its part-ownership of the composition itself.

This demand of sharing future payments that are meant for the creator in order to continue doing business is a practice not looked kindly upon in American commerce or by American consumers. It is akin to a recording artist taking credit for writing a song when the artist had no part of the creative process. What’s worse, the networks and motion picture studios demanding this ‘credit’ are creators themselves who should understand the systematic degradation of a creator’s rights that this practice has put in motion.” (Applause)

I’m going to leave the legal issue aside for the moment. That can be discussed another time. What I want to focus on is that I think our best weapon against this type of practice is sunlight, exposure, public pressure on these companies that are basically asking creators to pretend that somehow the motion picture studio or network had anything to do with the creative process, and therefore deserves any of the downstream performance money. Or even the worse practice of re-titling the composition for the false narrative that somehow they were part of creating it. This is a practice that I know has been going on for some time, but it feels to me – and as I talk to your members – that its getting more prevalent; that the networks are getting more aggressive about it; that you’re basically being put in a situation that is basically blackmail, basically a choice of not doing business, or doing business under terms you consider reprehensible, and that is not a fair choice to force you to make.

When this op ed runs today we’ll do our best to make sure that it’s read by many, including those in Congress and the administration in Washington that deal with these motion picture studios and networks. We’ve had some success putting public pressure on individual companies to stop the practice, but it’s clear to me we need to do a better job of doing that. I’ve now reached out and spoken personally to Beth Matthews at ASCAP, Michael O’Neil at BMI, John Josephson at SESAC and Randy Grimmett at GMR, and together we are committed to looking for ways to help stop this practice with regard to how they do their business, and I thank them for their willingness to engage with me in a process, working with MPNA to do something about this very bad practice. (Applause)

The second thing I want to talk about before I get to the slide presentation – and this is what came up from my discussion outside – is I want to talk thematically about something I think we as an industry are very bad at. And what I’m about to say is probably going to be controversial, it’s probably going to piss some people off. It’s something that I’ve said in different forms many times, in many places, and it’s something I think we have to focus on, and I’ve never talked about it with regard to your particular industry, but I think it’s relevant. Let me start by giving you the thematic overview of what this is about.

We’re in a battle over the value of music. We’ve been in that battle for a long time, it’s had its ups and down. It’s a battle that will never end. But what I’m increasingly concerned about it we’re letting other issues distract from the true battle. So I posit this: the value of our music is more important than the process by which we license it. I’ll say it one more time: the value of our music, is more important than the process by which we license it. Let me talk about it in three different areas where I see it playing out, the third one being in your world.

First let’s talk about mechanical reproductions. In the U.S. songwriters and music publishers have a compulsory license when it comes to mechanical reproductions. Now we can question why we have a compulsory license and a 1909 law intended to regulate player piano rolls should be in place today so that Google, Apple and Amazon get anti-trust protection against songwriters, but we have a compulsory license. Every five years we go to a trial and three judges that make up the copyright royalty board decide the value of our property, and we are in a battle over what that value should be. Unfortunately, instead of being in a conversation about how much we are paid for our mechanical reproductions – which today mostly represent interactive streaming companies, so we’re talking Apple, Amazon, Google, Spotify, Pandora Interactive, Tidal, Rhapsody, the new iHeart radio service – that is the mechanical reproduction world. Downloads are basically dead and physical product on its way to dying.

Instead of focusing on the value of what it is we’re being paid, we’re engage in a debate over how we license it. For those of you who are not in the business of mechanical reproductions let me explain briefly how this works. If you are an interactive streaming company and you want to open up a shop with 40 million you basically have to take three different licenses: You must go to the record labels, who are in a free market, and you must negotiate the value of the sound recording from that record label. Only after you have agreed on a term can you then put that song in your library and offer it to your consumer. That is a practice that’s well-understood; there is only one owner of the sound recording, and record labels have been very successful in the free market getting fair value for their sound recording. They’re receiving anywhere from 50-60 percent of the revenue generated by these companies. In some instances, like with Spotify, they’ve taken equity stakes in a company that may go public for $16 billion. That’s the licensing process from record label to interactive streaming companies.

On the publishing side, we tell them that they need two licenses: one is a performing license and the other is the mechanical license, which is a compulsory license – we can’t say no; the court tells us what the rate will be. Unfortunately for these [digital streaming] companies, they don’t know how to get that license because we as a community haven’t figured out how to give it. It made a lot of sense in the old days when we licensed record labels for individual records. They would come to publishers and say “These are the 10 songs, how do we license them?” And they would license them and put the record out. Instead, I had Amazon in my office saying “How do we license 40 million songs tomorrow?”

There’s no database that tells them who owns what. The record labels will not pass-through the publishing, like they did for downloads: When Apple sold downloads, understand, Apple never dealt with the publishers for mechanical reproductions. The label gave them the publishing, they paid the label and the label was supposed to pay us. With interactive streamers the labels don’t do that. So the companies have two choices – they can do a direct license with the publisher for what that publisher represents, or they can use the compulsory license process in section 115 of the Copyright Act and serve what’s known as a ‘notice of intent,’ or NOI, on the copyright owner. If they do either then they’ve licensed the mechanical.

All the companies in this space, that’s what they’ve done. They’ve either tried to take direct licenses or tried to file an NOI on behalf of every partial owner of every song in a 40 million song database. Well it’s not going to surprise you to know that without a blanket license option, without a database that tells them where to go, and with us insisting every song has fractional ownership, they haven’t done it very well. They have not done it properly. So what’s started to happen is there have started to be lawsuits filed against these companies for violating copyright because they did not license the mechanical part of the publishing need properly.

Spotify has been hit with two class actions, two other lawsuits in the middle district of Tennessee, and now several other publishers who have opted out of the class action may sue them directly. NMPA settled with Spotify and brought probably high 90 percent of the industry into that settlement. Some of those lawsuits are still paying out. What’s going to happen next is probably Apple’s going to get sued, Amazon’s going to get sued, Pandora’s going to get sued, anyone who enters this space is going to get sued because it is practically impossible to license this content properly.

Now, for copyright purists, they’re going to say “If they don’t have a license, just don’t put it up in the store,” and that’s right; they are copyright infringers. Don’t misunderstand my message. They are violating our copyright when they put songs up in their store that they don’t’ have proper licenses for. My point isn’t whether or not whether they’re copyright infringers, my point is what are they trying to do? These are companies that are selling paid subscriptions that are saving the music industry. We can fight about the rate, and we should because they’re not paying us enough, but because the licensing system is so broken, everybody’s talking about the process instead of whether we’re getting paid fairly. This is a situation that needs to be fixed.

I think you’re going to see legislation introduced in Congress in the next several weeks that would attempt to fix this. It’s legislation being negotiated by publishers, PROs, songwriter groups and the digital media companies that take these licenses. But I want to tee up what’s really important: What I think is important is the value of our song; what I do not think is as important is that we tell them that they have this puzzle to figure out with no road map, not blanket [license], and if they mess up we intend to sue them as a community. That’s not the right way to go about it, in my opinion.

I think a lot of the anger that’s fueling these lawsuits is that they don’t pay us enough. It’s not because we’re that upset that they tried to serve us NOIs and failed in some cases. I think we’re upset they don’t pay us enough and now we have caught them in a copyright trap and we’ll punish them. Let’s focus on what they pay us. But I don’t think it’s fair to say go find the partial owners of 40 million songs, you have no road map, and if you don’t we’ll sue you. And I also don’t think it’s a good idea to tell them to take songs out of their libraries when we’re in a battle for the hearts and minds of music consumers to pay for a music service every month. You’ve got YouTube out there for free that pays us crap. You’ve got Spotify that has a free service to the consumer that’s based on ad dollars which we can debate about which does not pay us well. Then there are paid subscriptions that are offered by Apple and Pandora and some by Spotify, and that is what’s going to save our industry.

The second place we don’t license well is the performance space, which is a very different system than the mechanical world. In the mechanical world we have a compulsory license, we can’t say no, the price is set by three judges in Washington, but there’s no entity to give the compulsory license. In the performance world, our performance right is not regulated by law. It’s a free market right. However, in 1941 two companies that are in the business of collecting this kind of right were put under consent decrees, and those consent decrees never end. ASCAP and BMI are told, based on a 1941 analysis that said the fledgling broadcast industry needed protection from the songwriters, that today ASCAP and BMI operate like they have a compulsory license. They can’t say no. They have a federal judge in the Southern District of New York that sets their prices, but they give a blanket license for what they represent. And for a long time that system worked just fine. Licensees needing a performance license would go to ASCAP, BMI and SESAC and get a blanket for what they had, and you never got sued for copyright infringement if you did that, because you were covered, having all of the rights that you needed for public performance.

In that world, the performance world, you didn’t need to know who owned every fraction of every song. You just gave a lump sum to the society and they worried about who owned every fraction of every song. So if you were a broadcast or digital radio station, or a bar or hotel, or anyone who took a performance license, you would negotiate a deal that was based basically on market share, you would pay basically based on market share and then you would walk away, not worry about ownership. That also is changing. You have now have a fourth PRO, GMR, that is not regulated by a consent decree. You have SESAC that is not regulated by a consent decree, and you have ASCAP and BMI who are increasingly making a convincing case they should not be regulated by consent decrees.

But the problem we have in the performance space is that when the licensees realize that if a GMR says “No, you may not have our license,” which is something they have a have a right to do under the law, that the licensee doesn’t know what to do about that. They’ve never had to deal with that. If we’re being honest, SESAC, the ‘free’ [not ‘compulsed’ to license] PRO never really said no to licensors. It always got worked out. If you are a radio station or bar or restaurant, you know exactly how this works. If you’ve got a friend who works in a bar or restaurant you’ve heard this story: “I got a knock on my door it was ASCAP. They wanted money.” And BMI, and SESAC, and now they might get a fourth knock.

What if they say ‘I’m done! I’m not going to play all that. I’m just going to play ASCAP and BMI music. I don’t want your license GMR! I don’t want your license, SESAC! Go away.” How would they do that? How would they know what not to play to avoid getting sued? The answer challenges those of us who believe strongly in copyright, like I do, with the business realities of what we’re trying to do. What are we trying to do here? It’s the value of the performance license that matters, it’s not so much the process by which we license it. So if we want a free market for performance rights, which I do; if we want ASCAP and BMI to be freed from the unfair rules they’re put under and they do the best they can under those unfair rules if we want SESAC and GMR to succeed in negotiating a true market value for their license, we cannot take the position that it’s an infringement trap.

So you’ve seen a couple of things happen. ASCAP and BMI announced a few weeks ago where they are working to integrate their databases – one, to define conflicts and clean them up, and two, so that a licensee can go into one portal and see what’s owned by both PROs, ASCAP and BMI. It’s a positive step forward. They’ve put a lot of work into it and I applaud that, but it doesn’t include yet are SESAC and GMR. So if you go into this portal, which they’re expecting to launch next year, and you see that one song is 40 percent owned by ASCAP and 40 percent owned by BMI, who owns the other 20 percent? Understand what our [NMPA] position is. Our position is that when you take the ASCAP license and the BMI license you’re only getting the fraction of the song they represent. Our position is that if you play that song without the other 20 percent license you’re an infringer and you can get sued. Again, focus on what we care about: the value of the performance license not the process by which we license.

The reason I’m talking about this is I was hearing about the requests you’re getting increasingly for international licenses with production music, and it makes total sense. The business models have changed. Just like in the mechanical space, where we’re not licensing CDs anymore we’re licensing Amazon to do 40 million songs. Just like in the performance space, where we want other PROs to be able to negotiate a fair price, it’s also true in production music where you have Netflix, where you have Amazon Prime, where you have others that want a worldwide license. We are running into problems in our inability to license to the new business model. I ask again, what is important to you? Is it the value of your production music? Or is in the process by which we license it? If you agree with me that the important fight is the value, we need to get our act together and figure out how to license properly.

We have to do it in the mechanical space, which is probably going to take legislation; we have to do it in the performance space, which I’m hoping is going to take simply business reaction to the problem and not legislation, but I’m worried about legislation if we don’t fix it. And it’s got has to happen in the production space and synchronization space, and that is a challenge I throw back to you. How do we start licensing the models of today and the future instead of getting caught up in these historical practices of how we used to license music, because that’s not what’s important anymore, it’s the value. Now talking about the value, this is a chart of data the NMPA has been collecting for 4 years that shows you the value of U.S. publishing and songwriting industry: In 2013 the industry was worth about $2.2 billion.

From 2013 to 2014 we actually saw a continued drop to about $2.152 billion. Most of that drop was the continuation of the slide of the loss of mechanical revenue, because of theft problems, and also a transition from an ownership model with albums to an access model often involving singles. But what happened in 2015 was remarkable – the industry jumped forward to a value of a little over $2.5 billion. In 2016 it continued its growth to just over $2.65 billion, and while we’re not even through with 2017 I will predict that growth pattern is going to continue.

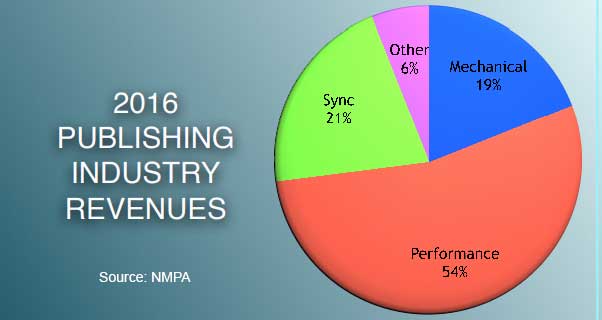

Our industry is experiencing growth. Of course that begs the question why? What’s driving the growth? One thing we do as the NMPA is ask members to confidentially provide their revenue figures, which we ask they divide among four basic categories: mechanical, performance, synch and other. Then we go back to the top 100 publishers, which represent over 90-plus percent of the market, and ask them to break it down further. In the mechanical space is it physical? Is it download? Is it a type of streaming? In the performance space the PROs use the categories that they report on: Is it television? Is it broadcast radio? Foreign? Generalized? Digital? In the synchronization space, is it coming from television? From movies? From advertising? From YouTube? And in other categories: Is it lyrics? Or something else. And we analyze this data so we can understand what’s going on in the industry.

What I would like to do for the production music industry is a similar exercise. We’ve been in discussion with the PMA for all PMA members to confidentially submit their revenue on an annual calendar basis and what we would then do is turn around and give you reports studying the industry so you can follow the trends and know what’s going on. That’s something I’m hopeful we’ll be able to work out and that all of you will participate in.

What we’ve learned from that exercise in regard to most publishers is that in the performance space you are seeing continued growth. It is coming from a lot of the traditional sources that are not going down, like broadcast radio, television, cable; but you are seeing significant growth in the digital space. Now, when the PROs report what they mean by digital they don’t really break it down: it includes interactive streaming (which is part performance); it includes non-interactive streaming like Pandora Radio, iHeart Radio, XM Sirius Radio. It includes things like YouTube. All of that is bundled in as digital. That’s driving the performance growth which is now representing more than half the industry income.

Mechanical, at 19%, is fascinating to me because, as mentioned earlier, you are seeing the near-death of downloads, the continued path toward extinction of physical product, yet we had growth in mechanicals from (2015-2016) only because of the mechanical part of interactive streaming. So the typical split is about 50/50. Interactive streaming will pay about 50 percent performance/50 percent mechanical. Half of the interactive streaming activity is driving growth over the loss of physical and download revenue. It’s incredible. That’s why it’s so important to see the success of these interactive streaming companies.

In the sync space, 21 percent, it has overtaken mechanicals. A large part of that is because of the growth of what you all are doing here. In the other category I continue to see lyrics drive value. Just yesterday Amazon put out its top requested lyrics from their [Alexa] devices. If you go to YouTube, often the most popular videos are lyric videos, not the official video from the artist. Consumers love lyrics, and as an industry we used to give them away. Now they have real value.

Those are the issues that are driving revenue growth for the industry. If you’re an individual company, an individual songwriter, you may or not have felt this growth yet, depending on your business model, depending on your success, but as an industry we have turned a corner from the challenges of the theft models and the shift from ownership to streaming models where we are now in a period of significant growth, and I would go back to the main point: what’s driving growth will be our ability to license new models. That is what will drive the growth. That is why I’m so insistent that we challenge our old ways of licensing, break them down and rebuild them in a way that works for the future, because as an industry we’re not very good at it.

A couple of quick updates about Washington: I mentioned the legislation likely to be introduced in the next few weeks. It will help every songwriter, music publisher and PRO. It’s something we’re very excited about. And we’re hopeful it will also be backed by the digital music companies that are our business partners. We can fight with them about value and work together over how we license them. That’s what that’s about. We just finished a copyright royalty board trial – we spent two-years in trial. MPNA represented the industry against five companies on the other side of the courtroom: Apple, Amazon, Google, three of the five largest companies in the world, and Spotify and Pandora. We are asking for radical changes in the way mechanicals are paid, and we’re waiting for December for these three judges to tell us what the rate is going to be for the next five years. One of the key things in the legislation that’s going to be introduced is changing the way that these judges set our prices. To be clear, I don’t want judges setting our prices ever. But as long as they do they should be using a willing seller/willing buyer rate standard, instead of the one they use now, which artificially depresses our prices. At the Department of Justice, BMI continues to fight the good fight challenging the Justice Department’s interpretation that somehow the ASCAP and BMI license is a 100 percent grant of every song where they represent a fraction.

This was the [Obama] administration’s Justice Department’s opinion about the consent decrees. The Copyright Office told them they were full of crap, and the judge that oversees the BMI consent decree has already ruled in favor of BMI, and now we are on the the Second Circuit on appeal, and we are supporting BMI in that fight and we hope they win and we think they will. Beyond that, there are more things the Justice Department can do for us. It is time to challenge the propriety of consent decrees that were put in place in 1941 to protect a fledgling broadcast industry. So it is time to go back and ask this new administration that may have different views on anti-trust and ask ‘Who needs protection from whom?’ Is it really Google and Apple and Amazon and the broadcasters that need protection from the songwriters? Because that’s how the consent decrees are being applied. It’s insane. I think we’re going to see some action at the Department of Justice. (Applause)

Comments are closed.