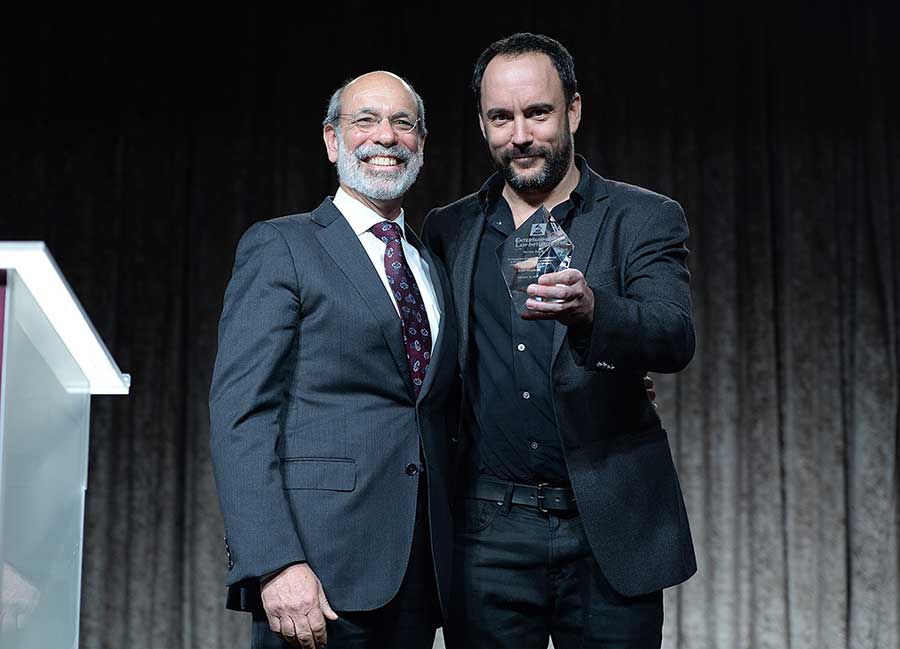

Music attorney Elliot Matthews, left, accepts the Grammy Foundation’s Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award for a distinguished career. (Photo: Michael Kovac/WireImage)

As a longtime attorney for artists, Elliot Groffman is no stranger to taking on record labels, but to hear him recount his career highlights and assess the current state of the industry, one knows he is a conciliator, and that like every top businessman, he knows the road to a sustainable future is paved with win-wins. Groffman, a partner at Carroll, Guido & Groffman LLP, on Feb. 10 received the Recording Academy’s Grammy Foundation Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award over lunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel, was welcomed to the stage by Dave Matthews, who Groffman has represented for more than two decades.

“In my life I was very lucky to have been part of some amazing relationships that I’m very grateful for and one of them is Elliot Groffman,” Matthews, a singer, songwriter and two-time Grammy-winner, proclaimed. Matthews — who earned high marks from attendees for his comedy chops — movingly described how when he was just starting out, he “relied on other people’s ambition” to get ahead. One of those people was his manager, Coran Capshaw, who exposed The Dave Matthews Band and helped build a following. “I started playing little clubs, and people came out every Tuesday, and then there were too many people to fit in the club. And I played a show and met Coran, who said, ‘Play at my club.’ Then he was generous enough to say, ‘I’ve got another club, play at that club too…every week,'” Matthews said, prompting laughter at that hybrid between help and exploitation.

“It grew quickly for us, but not too quickly,” Matthews recalled. “Back in the ‘90s when people still bought CDs, we played a lot. That’s all we could really do, we played for 10 people or 500 or a few thousand, whatever we could get.” Matthews said he and the band liked it that way, “and Coran liked it too.”

Another of those who was ambitious on Matthews behalf was Groffman. “I remember, Coran was like, ‘Elliot’s the real deal. He’s smart.’ By the way, Elliot was the real deal,” Matthews told the audience of about 450 people. Immediately apparent to Matthews was that Groffman “was really into music and really excited about it. He couldn’t fake it, because he was there, and he was like ‘I wanna be a part of this!’ You may not be a fan of my music,” Matthews shared in an aside. “That’s your problem!,” he intoned, prompting explosive laughter. “But Elliot really was. I felt that.”

Matthews went on to describe “musicians generally, the ones I know, are not great planners. I’m not,” he said, describing himself as ” a caveman, when it comes to any of this. It’s like, ‘Guitar! I like to make a noise! Wernk, wernk, wernk! But having people like Elliot defend my right to make a sound, and having someone who believes, like Elliot does, that the sound is worth something — that is spectacular.”

With people like Groffman defending music, the creative process is in good hands, Matthews concluded. And hearing Groffman expound for 20 minutes with grace and humility about his extraordinary career, one could not help but agree. What follows is the transcript of Elliot Groffman’s ELI Service Award acceptance speech:

In the beginning…

Thank you Dave, for that amazing introduction. I don’t know what to say. And Geiger, following Geiger. This internet thing, I think it’s going to catch on. I hope to use it someday. And thanks Neil Portnow and the Grammy Foundation. It’s humbling to stand up here in front of my peers and be grouped with your past honorees, these people I’ve grown up admiring and learning from during what I have to admit is now a 30-plus year career. It is kind of rare to get time to think about these issues, but I guess I’m up here as part of that generation that came of age in the chaos of the digital era, not to mention the global economic recession of the mid-2000s, and whatever we can call what we’re going through today. And I think all of us derived strength from our mission to see our industry through this era.

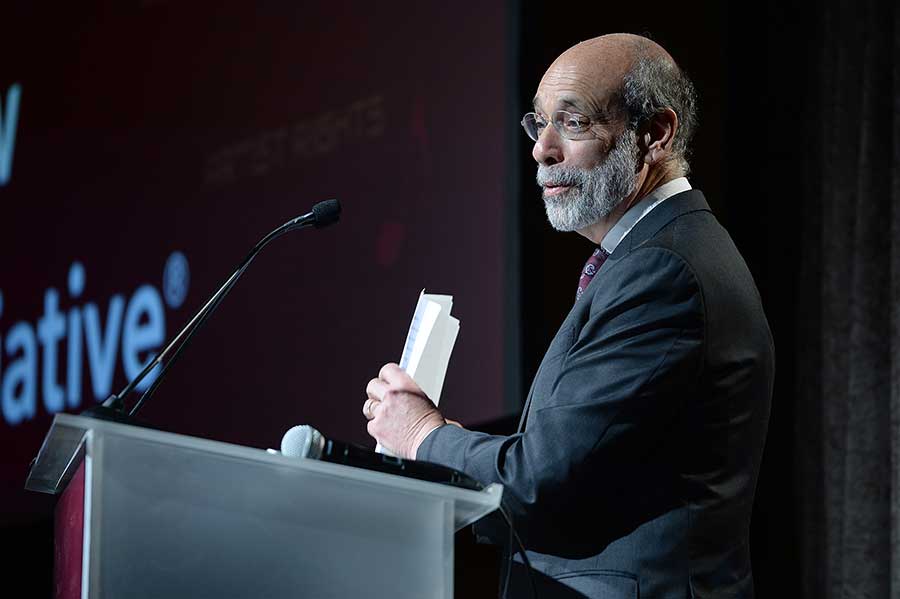

Elliot Groffman said handling 360-degree deals that give labels a piece of every aspect of a musician’s income, is “the key challenge” for artist lawyers. (Photo: Michael Kovac/WireImage)

And working with Dave and Coran has been the core relationship of my career, from which I was able to grow as a lawyer and a person and work with so many amazing artists, and put into action the ideas and concepts that I first worked on with them. I was able to enter that zone that I’d always dreamed about, where I was able to work with extraordinary musicians on cutting-edge business. And it’s funny, listening to Geiger talking about the future of the business, and thinking back to the early ‘90s and realizing how limited the options were, right?, for an independent artist: you could put out an indie record, you could develop your local touring strategy, as Dave beautifully described, into a regional and eventually a national strategy, through a combination lenient taping strategies, communicating with your fans, merch sales. And today you can do so much, posting tracks, albums, selling tickets, engaging in a whole array of activities that were not available. So I take my hat off to Coran, Dave and the band, for creating that family relationship with their fans, so that by the time Under the Table and Dreaming came out you had a base that helped grow and sustain the kind of long-term career that you deserve. So thank you.

As I may have mentioned to some of you over the years, as a teenager growing up in central New Jersey, just a stone’s throw from Asbury Park, I was lucky enough to watch a young Bruce Springsteen and the guys play at local clubs and schools and other venues. My friends and I always knew he was going to be a huge star, and our bands, mostly dreadful, I might add, did our best to get on bills with his bands and were especially thrilled they allowed us carry their equipment. I also used to hang out as often as possible at Jack’s music shop in Red Bank, listening to records and leafing through Billboard and Cashbox. What was a producer, I wondered. A&R executives? Who were these people in the music industry and how was I going to worm my way in there?

So of course I was a typical kid of the ‘60s listening to as much of everything as I could. The British Invasion, Dylan, Hendrix, The Who, and so many others. Although when the older brother of one of my buddies came home from college for Thanksgiving of ’68 and turned us all on to The Grateful Dead, things changed. (Laughter). My poor brother Peter still bears the scars of covering for me that August weekend in 1969 when as a junior counselor at camp in the Poconos I joined the college kids and saved up our days off and went to Woodstock. It was a wild weekend for a 15-year-old to say the least. But the bottom line is I don’t think I really had a choice but to pursue a career in the music industry, and I truly can’t envision what I would have done if I hadn’t gotten here today.

The Grubman Years

I started paying my dues after law school with a labor law firm, then became a copyright litigator with Jonathan Zavin, now at Loeb & Loeb. I did a lot of publishing litigation, but most memorably we sued jukebox owners for BMI. I will never forget the call from Little Joey Naples from Chicago as he explained what would happen to me if we didn’t withdraw the lawsuit. (Laughter)

On the side, I started working with some baby bands, mainly drawn from the emerging hardcore scene of the early ‘80s. Those rock hotel shows downtown were insane, and unfortunately there were some pictures of me with my client Overkill to prove it, one of them you can see in your program today. I was lucky enough to join the [Bruce Springtseen attorney Allen] Grubman firm in the mid-80s, and all of a sudden I went from the bullshit fringes of the industry, as [Grubman’s then-partner] Artie Indursky so delicately put it, (laughter) to the heart of the matter. As the junior guy on the team for Springsteen and Mellencamp and so many others I was thrust into the highest levels of the business, and learned so much about records, publishing, touring, merch and everything else. I will never forget that first week, though, sitting at my empty desk in that empty little office with nothing to do because my new boss was too busy to even talk to me. He did walk in the first day and threw a folder of agreements on my desk and said “Read those.” So after several attempts over a couple of days to get in to see him, I poked my head into the office next door and asked Don Friedman, “What should I do?” And in classic fashion he peered over his glasses at me and handed me a stack of documents and said, “Revise these.” So…

Groffman says, “you’re looking at one of the happiest human beings in the world. I live and breathe music, and I work in the music industry.” (Photo: Michael Kovac/WireImage)

All joking aside, professor Friedman mentored me through deal after deal until I got pretty good at saying “No,” Uhh…I mean understanding record deals! (Laughter) When I finally got to shop my first client a couple of years later I was itching to put all that knowledge to use. And luckily that band was Living Colour. The band’s breakout hit, “Cult of Personality,” became one of the most influential songs of the late ‘80s, and it was the first time I got to work with an artist for whom social and political issues were an essential part of their identity. It was an amazing experience which will never be duplicated for me. But of course the best part of the story is not about my personal evolution but about the evolution of this business.

When I joined Grubman everybody was excited that the term of record deals were down to seven or eight albums. (Laughter) Right? The mid-80s were plagued by a huge slump, as Geiger told us, as vinyl sales plunged and consumers rebelled against expensive records that had only one or two good songs and were loaded with filler. Sound familiar? Then the CD boom came along and business had an unprecedented growth spurt, which paradoxically created the illusion that as an industry we knew what we were doing. But following explosion of Nirvana and Pearl Jam, with whom I’ve had the privilege now of working with for over a decade, it seemed like every label needed to sign-up rock bands, and my colleagues and I were having a blast. Two firms, three firms, video commitments, tour support, we negotiated tooth and nail over creative control issues, because of course every one of our clients knew what they were doing, right? (Laughter)

My classic comeuppance came in the office of an unnamed label chairman and his team during the first album cycle of one of those bands that was not going so well. I stood there waving the pages which detailed all these amazing commitments I had negotiated, and which the label was now hemming and hawing over, and after hearing me out, the chairman looked around the room, and turned to me with a friendly smile and said, “So sue me!” (Laughter; and perhaps worth noting that the lawyer sitting next to me whispered, “That was actually a good idea!”) I hadn’t thought of that of course. So with my tail between my legs I went back to the client and suggested they might have to adjust their expectations a little bit.

Although in the early to mid-90s we were still more or less working within the confines of traditional deal structures, it was in the live world that things started to change. The earliest festivals had begun as touring properties. I got to work with the late Chip Hooper on the board of Bonnaroo, the alternative to Lollapalooza, jam-packed with kids celebrating an alternative music and lifestyle. This was the first place I had saw The Dave Matthews Band. A couple of years before my colleague David Weinberg introduced through a friend to the band’s corporate lawyer, Philip Goodpasture, who connected us with Coran and Dave, and it was also through that relationship I really got to know Chip, who was not only an extraordinary agent, for DMB, Phish and others, but a talented photographer and a special guy. Later on we’d collaborate on the transition from Monterey Peninsula to Paradigm, where Chip helped create a team with Marty Diamond, Paul Morris, Tom Windish among others that will be an enduring legacy, and one I was proud to play a role in.

Live Thrives

Meanwhile, Coran and Chip saw that since DMB was an amazing live band, there was now an epidemic of poor-quality and expensive bootlegs in the marketplace. After realizing it was going to be impossible to counteract the flood, Coran and I went to [then RCA Music president and CEO] Bob Jamieson and said, ‘We should put out some live albums to counter-attack the bootlegs. Let’s give the fans hand-chosen, good-quality, well-priced concert albums instead!’ We had an amazing relationship with Bob and the other folks at RCA.

But Bob said, “Live albums don’t sell,” citing the standard industry line. And we said, “Like Live at the Fillmore for example?” And he said, “Well, that was in the old days, boys, you’ve gotta get with it.” And almost as a flipping thought on our way out the door we said, “Hey, you know what, we’ll pay for the albums and you just distribute them.” And Bob said “Sure.” And two million copies of Live at Red Rocks later we felt pretty good about the decision.

Bob did get with the program after that, and did a series of releases, which over time have now morphed into the regular posting of shows for deep fans, not only DMB and Phish but Pearl Jam and others, become part of the system today.

When I joined with Rosemary Carroll and Michael Guido in 1998 we shared the belief that the business was on the edge of irrevocable change. Michael was at the ground level of the hip hop business and advocated strongly for its recognition by the mainstream industry, culminating eventually in the ground-breaking Rock Nation deal with Live Nation. Rosemary of course was there with Patti Smith, Kurt Cobain and others who shook things up. We believed that with the technological upheaval that was at hand – and remember, this was… Nashville was still a year or two away from impact – you were either part of the problem or part of the solution; Michael always had the best phrases. So our mission statement was to stay close to the artists, stay close to the innovator-entrepreneurs who would be on the front lines.

We had the opportunity to work not only with the talented men I’ve mentioned already, but women such as Patti, Roseann Cash, Brandi Carlile, Bonnie Raitt, so many others who touch every corner of the industry. The exciting part of a small practice is you never know what the next phone call will bring, what potentially wacky ideas will come across your desk. I do laugh when I think about Rob Cohen’s face when he joined us in 2000 after a career at Sony and BMG, as he would try to wrap his head around the crazy things we would ask for from his former corporate colleagues.

Elliot Groffman and Hilary Leff, happily married for 32 years and proud parents of two grown children. (Photo: Rob Rich)

The lid had come off. The old world order was gone. We thrived on fighting for our artists to make sure that they’d their due. Not every day is easy, and I’m certainly not very zen-like. As Julie Swidler mentioned in her speech last year, “the industry is populated with dreamers or telephone screamers.” I’d like to think I’m both, actually. Lord knows I can be loud, and even a bit profane, but I believe it stems from my passion in fighting for our artists and our clients. I could not have taken this ride without the support of my partners, Michael, Rosemary and everyone at the firm, even the Nashville guys, our TV colleagues here to celebrate with me, and I thank you all very much. (Loud applause.)

I wouldn’t be here without the support of my family, who are all here today as well, Hilary, my wife of 32 years, who has no doubt gotten a little tired of a lot of late nights and loud music and me running through the door saying, “You’ve gotta hear this!” Luckily we have kids who took the brunt of a lot of that. She and I are so proud of how Allison and Jonathan have forged their career paths based on passion. Allison and her husband are busy tackling the fashion world, and Jonathan as some of you may know is in his first year of law school – no pressure on anyone whatsoever. Seriously, you’re looking at one of the happiest human beings in the world. I live and breathe music, and I work in the music industry. I’m just saying I couldn’t have done it without the support of my partners, colleagues, friends and family.

Looking Ahead

So where does this leave us today? As Giger said, the industry of the future looks to be huge, and potentially lucrative, but very different from the one that exists today. It’s easy to say the business model has shifted, but everything that statement entails is massive in its implications.

There are vast numbers of alternative methods for bands to move their careers forward today, but each one has its pitfalls. As lawyers we need to help guide developing artists and work with their managers to figure out which strategies are the right ones. We need to be knowledgeable about the details of the deals with the DSPs so that we can be creative in making deals for the artists that want to go direct. There are alternative financing sources today, but which deals are worth doing and which ones you want to avoid. If you believe as I do that the most exciting times for our industry are yet to come, we need to devote ourselves to innovation and flexibility to continue to lure the next generation of lawyers, creative executives and others to join our industry and not be lured into the tech or banking worlds.

Also, In the overheated political environment that we live in today we need to aggressively use our role as artist representatives and partners to encourage the artist community to find its individual and collective voice and support the social and political causes that are important to them, and us, in the face of political opposition. (Giant applause and whoops)

For me, as an artists’ lawyer, the key challenge is how do we handle 360 deals. (Murmurs of assent from the crowd) If the future is so bright, can we get there together? Can both the labels and artist community thrive? I’m not here to debate whether the labels should be asking for these rights, although I’m happy to do so over cocktails with anyone who wants to join me later.

The key is, can we create a proper balancing act? Proper return for proper investment. I don’t’ have a problem with that concept, but at some point… Let’s say it’s been years since tour support or other extraordinary marketing expenditures are required for maintenance of that career. We need to be able to flip these deals and start to phase out these participations. Otherwise, what might arguably be a helpful inducement to a label to spend properly or even enthusiastically in the early days can turn into a windfall which will hurt the artist. We need a balanced and healthy ecosystem to nurture talent and provide returns so when we get to that bright, bundled future, we have a sustainable and balanced business model. I look forward to coming back in 10 or 15 years and hearing what somebody else has to say. Thank you very much. (Loud applause as the crowd gives a standing ovation)

(L-R) Grammy Chief Advocacy Officer Daryl P. Friedman; ELI Executive Committee Chair Henry W. Root; National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences President Neil Portnow; attorney and honoree Elliot Groffman; musician Dave Matthews; William Morris Endeavor head of music Marc Geiger; House Judiciary Committee Chair Bob Goodlatte (R-VA); and Grammy Foundation’s Scott Goldman, at the Entertainment Law Initiative lunch at the Beverly Hilton, Feb.10, 2017. (Photo by Michael Kovac/WireImage)

Comments are closed.